When I started writing my book entitled, All the Dancing Birds, an illogical and imaginative leap into the mind of Alzheimer’s, I started with nothing more than an interesting idea and a brave swallow. Within the first few pages into my story, I realized it would take more than just the observation of and love for family members and a friend with whom I had the privilege of interacting, during the course of their disease, in order to write a compelling story that would have meaning for others.

I needed to study. To know. To recall more than just being a frightened and ill-equipped family member or friend. I needed to find that jumping-off point where I could leap from my own ingrained sense of what is normal and right.

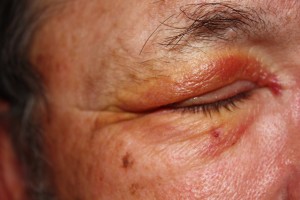

It helped that I had survived a brain tumor. That small fact allowed for one tiny emotion to surround every family conversation, every interaction, every Oh-Dear, does-he-really-think-there-is-fire-coming-from-my-purse? moment of surprise. There was always one thing that held us each together, that stitched the logical to the illogical in all those crazy-quilt conversations of reality-gone-different. I too had experienced a form of brain disease and that one fact made us lovingly similar.

So there it was!

The only thing that helped during every nonsensical, circuitous down-the-rabbit-hole conversation was reminding myself that my loved one suffered from a BRAIN DISEASE. Our only difference was that my disease was a golf ball-sized mass of tissue that had been REMOVED. Their disease couldn’t be plucked out and dropped into a stainless steel pan to be sent off to pathology. While I had been saved, my dear ones had no recourse but to ride out that A-Ticket of Alzheimer’s Disease to its final destination.

Thus, I found our connection through the non-judgmental aspect of empathy. Grand, whopping dollops of never-ending, fly-by-the-seat-of-my-pants empathy. It’s from that perspective that I wrote All the Dancing Birds. From a heart of Empathy with a capital E.

While my dearhearts were alive, without that me-too sense of connection, I’m sure our interactions would have been different. We would have had conversations where I’d have tried to insert and assert my sense of “reality” when all that was necessary was a simple act of what my mother called, “putting on my listening ears.” Without judging what was right or wrong, real or unreal, I was able to be an (albeit reluctant) observer. I tried very hard to be a person who didn’t remind my loved one that I’d heard that story already ten times in the last hour. I tried especially hard to be that person who took a diatribe of nonsense and, instead of letting it make me cry, allow the words to be assigned to whatever broken part of the brain that caused such an unexpected outburst. Meaning and importance was turned upside down and inside-out, shaken out and then swept up like so much spilled salt.

When it was all over, I empathized my way into writing a story from their perspective. From their heart. From THEIR mind.

Each of my loved ones, while in the vortex of their disease, had exhibited different behaviors, different mannerisms, different ways of coping. Whether they admitted it publicly or refused to acknowledge their illness, each knew they were very ill. Each struggled and hid and flailed through frightening days and even more terrifying nights. It was this amalgamation of their common set of behaviors from which I crafted my story.

All the Dancing Birds is now nearly done, the words are almost all in place, the prescribed number of manuscript pages is almost there. I’m just days from completing an illogical, upside-down, inside-out work of art in honor of my dear ones. How great is that?

Wish me luck!